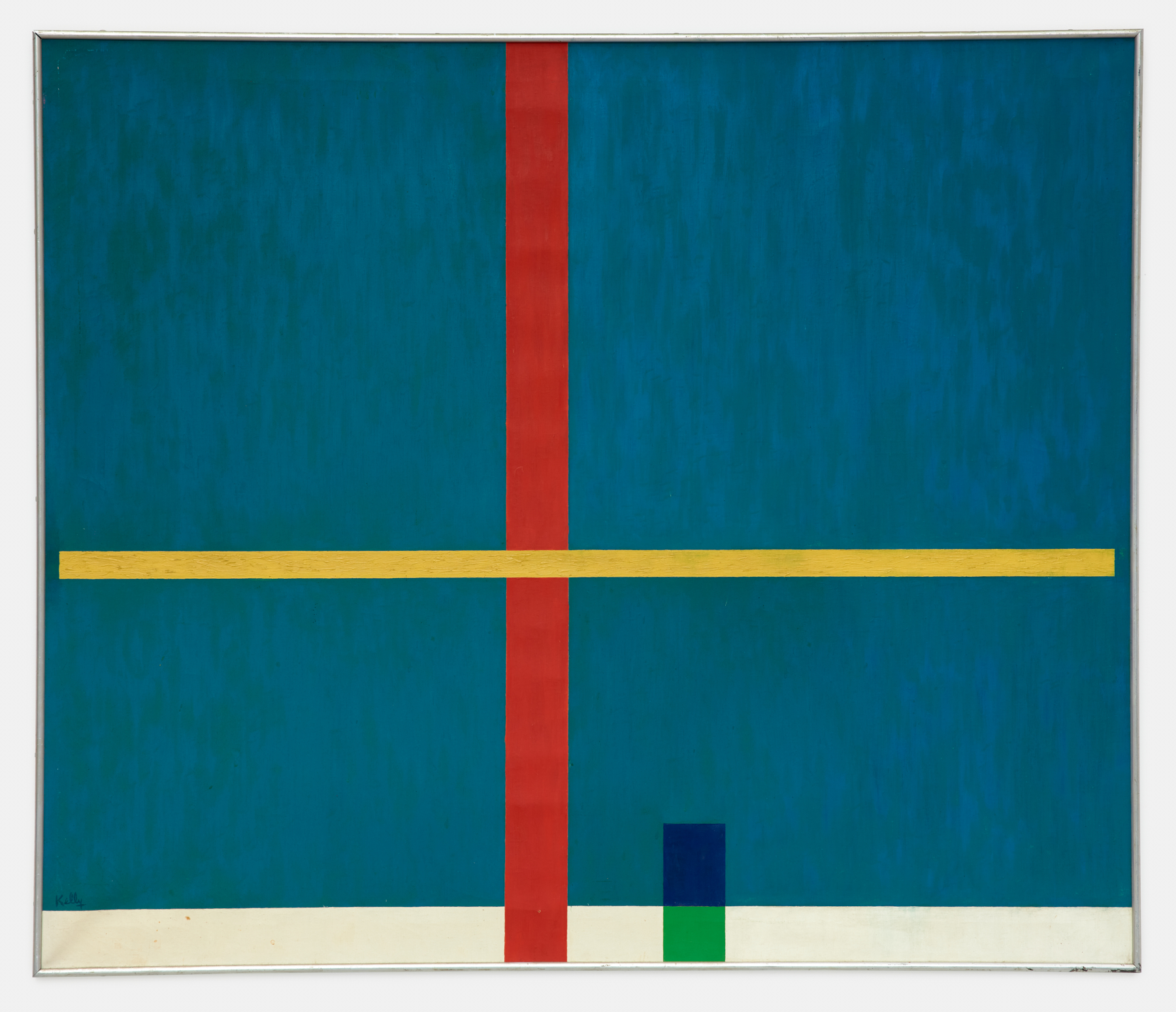

James Kelly, Xochimilco, 1963, Oil on canvas, 66 x 77 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Xochimilco, 1963, Oil on canvas, 66 x 77 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

The Necessity of Painting James Kelly: Seven Decades of Painting and the Origins of Bay Area Abstraction

March 31 through May 19, 2023

By ISAAC ADEN, May 2023

There are many painters who persevere with their art practices irrespective of widespread recognition or economic success. In them is a relentless appetite to continue painting despite the swings of current trends away from them or the lack of critical attention they receive. Even so, the question of letting the palette dry out for good is not a viable option. For these painters it is really all about the studio and the time spent standing in front of a canvas. The real questions emerge during the in between spaces of a painting’s completion, when the resolution remains out of reach and beyond a horizon. Painting remains for these artists a necessity.

James Kelly, Untitled,1948, Oil on canvas, 34 x 40 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Untitled,1948, Oil on canvas, 34 x 40 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

Thus, it is by no mere coincidence but rather through an unyielding determination that a painter can amass a lifetime’s worth of work. When looking at the totality of an artist’s oeuvre, I am always taken by the twists and turns that inevitably end up occurring, and how the need for the necessity of painting pervades through their lives. This truth was the case for James Kelly (American 1913 – 2003). Kelly’s exhibition Seven Decades of Painting: From California Abstract Expressionism to New York’s Downtown Scene at David Richard Gallery traces the artist’s oeuvre, presenting canvases from each decade which trace his own personal and artistic journey with painting. David Richard Gallery is known for mounting considered exhibitions which look at artists with demonstrated dedication to painting and in doing so have made considerable strides in their own work. James Kelly is a perfect example of this type of painter. His work is in the permeant collections of MoMA, The Whitney, LACMA, SFMoMA, and a considerable number of other prominent museums, and yet he remains relatively unknown. In this in-depth examination of Kelly’s practice, we can see his stylistic oscillation between hardedge geometric abstraction and a more expressive type of abstract expressionism. Kelly’s personal touch for abstraction was developed during the early 1950’s in San Francisco, where he was one of the pioneering bay area abstractionists.

James Kelly, Untitled, 1952, Oil on canvas, 33.5 x 25.5 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Untitled, 1952, Oil on canvas, 33.5 x 25.5 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly’s artistic journey was predicated on a bicoastal presence. In this manner His practice could be considered through the lens of Jack Kerouac’s seminal and historically concurrent novel On the Road. Just as Dean in the Kerouac’s novel, the path of Kelly’s paintings would take epic journeys often arriving in unexpected and divergent points from which they came. For Kelly it can be seen that it was really about the journey, not the destination. His own personal artistic journey would make multiple stylistic switchbacks arriving at seemingly polar aesthetic conclusions. He moved back and forth between the spectrums of language in abstract painting, from hard edge geometric abstraction to a more painterly form of abstract expressionism.

Kelly’s mature work from the 40’s would be marked by his own brand of geometric abstraction deriving from the genealogy of Mondrian and the Constructivists, however Kelly’s paintings had unique aspects which distinguished them, such as the small blue rectangle in his Untitled, 1947 which has the distinct quality of transparency. This single move drastically sets him apart from other artists or the aforementioned movements. During the 1950’s Kelly would depart for more painterly compositions in which the artists hand was central to the work. Kelly began to use brush strokes and cumulations of marks as compositional elements in and of themselves. They are akin to color field yet distinct in that the prominent brush strokes and mark making are propelled forward. Kelly’s paintings from this period are frequently made from dark or muted colors, whereas we can see the inverse being true in color field, generally speaking the color is the predominant feature and brush strokes, where they are evident, usually recede.

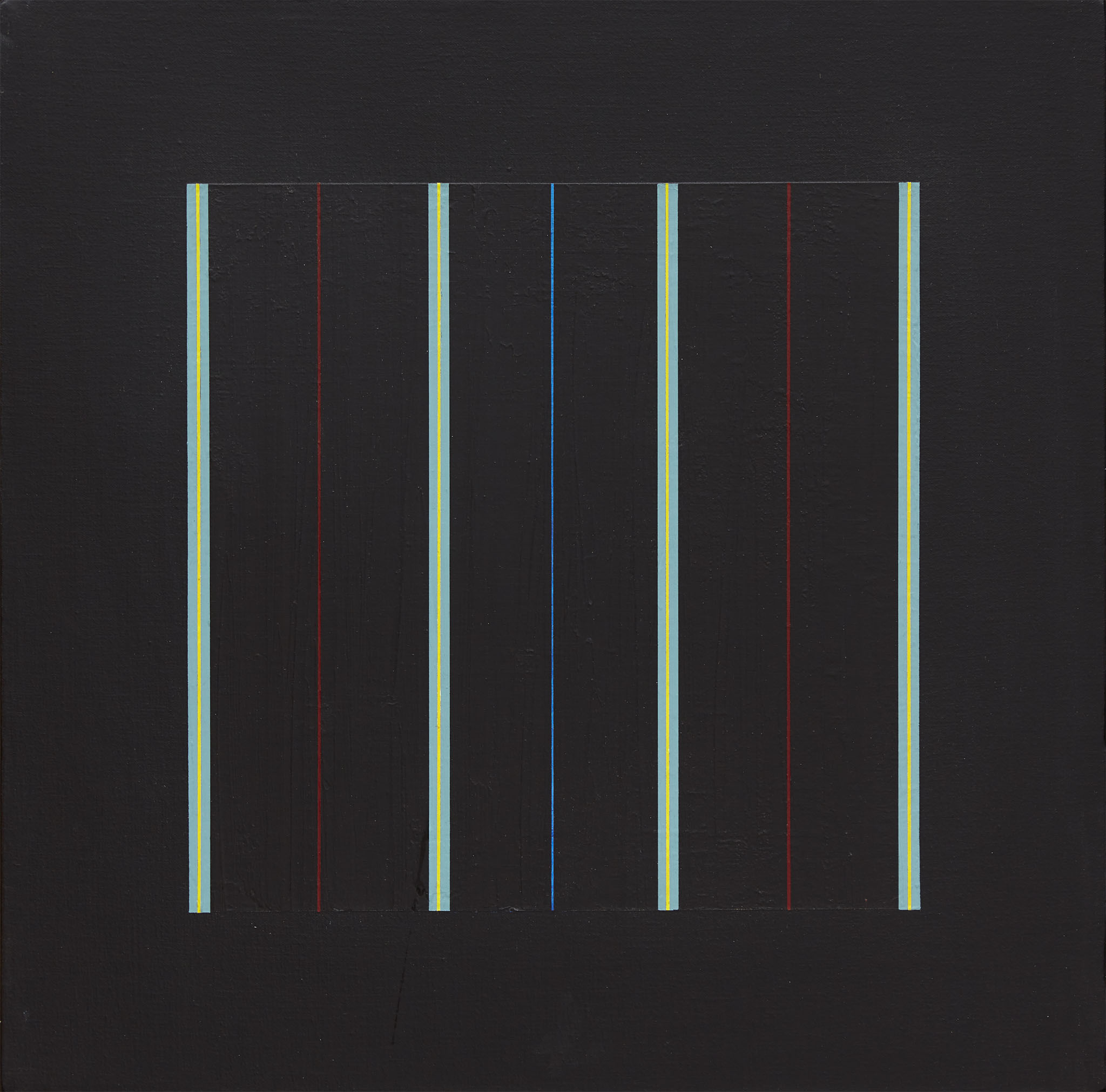

Upon moving to New York in 1958 Kelly’s work from the early 60’s would stop being about pure abstraction and he began to conflate abstraction with figural concerns often with a wonky sensibility which seems to have a relationship with pulp drawing. Today these works seem highly relevant and fresh, however at the time the predominant critics like Greenberg favored the nonobjective and were chastising artists who explored this brand of abstraction such as Philip Guston. Perhaps this shift in Kelly’s painting practice was because he had already explored abstraction free from representational content and felt there was inevitably more ground left unturned between cubism and expressionism. His approach could be seen as a kind of Proto-Post-Modernism. Kelly’s gestural strokes would be softened in the latter half of the 60’s his radiator series would pair vivid and often florescent color with hardedge geometric abstraction. Yet during this period Kelly’s paintings would be marked by soft and gradually curving forms. His strokes would be mitigated yet his hand would remain evident. His symmetrical shapes and compositions would seem to demand a rigorous geometry, yet Kelly would render these forms by hand resulting in a peculiar wonkiness which would distinguish them from other formalist approaches.

During the 70’s Kelly geometric abstraction would become more refined. His edges were taped, and his fields would often be made from highly impastoed surfaces made with a trowel. These workman-like surfaces would contrast his otherwise slick execution He again contended with the figural potential of abstraction even though the predominant language in the paintings were dominated by hard edge geometry. During the late 70’s Kelly’s paintings would reduce to lines and grids. A seemingly drastic shift occurred in the 80’s, perhaps Kelly felt painted into a corner with his reductive works. Kelly returned to a painterly form of abstraction which contended with figural forms loosely portrayed while simultaneously building up large sections of his canvases with cumulative fields of fat paint, of which the brush strokes were elevated to be content in and of themselves.

James Kelly, Blackfoot, 1965, Oil on canvas, 49.5 x 47.5 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Blackfoot, 1965, Oil on canvas, 49.5 x 47.5 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

To understand the stylistic shifts in Kelly’s work it is necessary to consider his biography and the context in which he painted. Kelly was born in Philadelphia. While working in a shoe factory, Kelly studied nights at the School of Industrial Arts and eventually earning a bachelor’s at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts, Kelly was also awarded a scholarship to the Barnes Foundation where he was immersed in the collection and exposed to Post-impressionism and Modernist art. Kelly was particularly impacted by the work of Vincent Van Gogh and said of him “Van Gogh’s paintings were alive – that tactility. Prior to that the paintings I had saw in museums were well blended, smooth. When I found him, it was an explosion.“Immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor Kelly enlisted in the Airforce where he would serve in the Pacific campaign. Kelly saved his pay to focus his energy exclusively on his studio practice once he was discharged. After the war Kelly moved to California to study at the California School of Fine Arts where Clyfford Still was a prominent teacher, Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt had also taught there. According to Terry St. John,

“Three events now seem to have been most instrumental in shaping the course of the Abstract Expressionist chapter of San Francisco art. The first and perhaps the most significant event was a sweeping change in the California School of Fine Arts’ faculty and educational philosophy. Douglas MacAgy became Director and replaced most of the faculty, with artists who not only experimented with radically new ideas but who encouraged their students to do the same. The next event that occurred was the influx of ex-G.I.’s into its student body. The final important factor was the post-World War II era itself.”

The GI Bill allowed young veterans returning from the war government funding for studying, this brought tremendous freedom to many young artists and helped develop the American graduate art departments across the country.

“For many like Kelly this freedom was also economic, thanks to the GI Bill that freed artists to focus on the work of making art, rather than earning a living.” -M. H.S, San Jose Museum of Art

James Kelly, San Francisco, 1951, Photograph by Phyllis Lynch. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, San Francisco, 1951, Photograph by Phyllis Lynch. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

Kelly gravitated to the energetic style of Hassel Smith. Art critic Thomas Albright would characterize Kelly’s early work as “volcanic gesturalism in which boundless energy was suggested through the accumulation of dense swatches and slabs of color that drove in surging rhythmic trajectories.” In San Francisco Kelly’s work flourished. Living in Fillmore with his wife, the painter Sonia Gechtoff, his building was dubbed “Painter Land” by the poet Joanna McClure. Kelly’s next-door neighbors were Wally Hedrick and Jay DeFeo.

Every great artist needs a champion, and Kelly found that in the curator Walter Hopps. Hopps included Kelly’s work in his seminal first exhibition in which Hopps installed abstract paintings on the merry go round on the Pasadena pier. Kelly’s paintings were presented alongside works by Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still while simultaneously playing jazz and static.

“In the summer of 1954, Hopps and (Jim) Newman spent time together in San Francisco exploring the work of a group of artists, most of whom came out of the abstract expressionist milieu that had developed at the California School of Fine Arts (which became the San Francisco Institute of Art). These artists, such as Hassel Smith, James Kelly, Julius Wasserstein, Roy De Forest, Sonia Gechtoff, Wally Hedrick, and Jay DeFeo, exhibited at a few dynamic galleries in San Francisco committed to new, local work… Hopps wanted to bring what he found in San Francisco to Southern California.”

“It was near Muscle Beach. It attracted the most totally inclusive mix of people—Mom, Dad, and the kids, …and other strange characters, and the patrons of a transvestite bar nearby. I got Ginsberg, Kerouac, and those people to attend. It’s amazing they came. Critics I’d never met before showed up. It had a big attendance”

Kelly’s work would remain one of Hopps primary focuses as he continued to develop his curatorial repertoire. According to Hopps, “The main people in my group shows were Sonia Gechchtoff, Paul Sarkisain, Edward Moses, James Kelly” Hopps would go in to include Kelly’s work in the second Action exhibition. Between 1952 and 1956 Kelly’s work was also frequently shown at Hopps curatorial incubator the project space known as Syndell Studio

Kelly would remain one of Hopps’ main artists. In 1957 Walter Hopps formed The Ferus galley with artist Ed Kienholz to exhibit contemporary artists from northern California and Los Angeles. Kelly was one of the original Ferus artists. Hopps was taken by the freedom found in the artists from the west coast, their work was quintessentially American; embodying manifest destiny, unbridled from the hewn traditions of east coast Abstract Expressionistic and the historical weight of European painting. Rather their influences flowed out of surf culture, the Beats, and jazz.

James Kelly, Elephant Walk, 1978, Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 48 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Elephant Walk, 1978, Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 48 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

The Ferus gallery was of historical significance, it represented the burgeoning California art scene and was instrumental in introducing abstract and contemporary art to the California. Many prominent artists would have their first solo exhibitions here such as: Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin, Ken Price, Larry Bell, Ed Ruscha as well as Andy Warhol’s first Pop art exhibition of Campbell’s soup cans. The legendary gallerist Irving Blum would be introduced to Kelly’s work as he became a partner in the gallery. Blum recalls the early state of California’s art scene in the following excerpt from an interview held in the Smithsonian Institutes archives.

“There were three or four galleries in existence at that time (in Los Angeles) …the gallery that seemed to me the most provocative and the most interesting, the one that I identified with right from the very beginning, was a gallery that was started the previous year by Walter Hopps and Ed Kienholz. Called the Ferus Gallery. They represented… artists all of whom were from California –some from up north and some from south. For example, people like Frank Lobdell from up north, Jay DeFeo, James Kelly, Wally Hedrick, Hassel Smith, Wally Berman certainly was part of the scene, from south; Billy Al Bengston, Craig Kaufman, Ed Moses, John Mason, Peter Voulkos.”

James Kelly, Italian Shirt, 1978, Oil on canvas, 20.5 x 20.5 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Italian Shirt, 1978, Oil on canvas, 20.5 x 20.5 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

What revealed itself as quite compelling from the research on Kelly and the development of the early San Francisco abstract art movement, was how genuine it was, it was strongly based in community rather than market commodification. The artists each sought to advance their individual work, but this was done through a shred experience and vigorous dialog about painting itself and what it could do. It was also about developing a cathartic experience through painting often as part of a means to address the horrors of wartime and the constraints of military discipline.

“George Stillman one of these veteran- students explained the psychological underpinning of the San Francisco School “We had all been fed up with regimentation, with being put in a uniform and told what to do. We were looking for a way out of that discipline a way to be individual, a way to be human.”, Still’s rejection of Cubism, Surrealism and an intellectual approach to art history spoke to students who were seeking a cathartic outlet for their wartime experiences.”

James Kelly, Toledo, 1989, Oil on canvas, 42 x 40 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Toledo, 1989, Oil on canvas, 42 x 40 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

Outside of metropolitan centers like New York, pockets of Artist exist in small communities often connected by their shared path as artists rather than their aesthetic stances. The significance of the small community was particularly true in the early stages of San Francisco’s abstract movement. The artists lived in proximity to each other, and the galleries would develop in their Fillmore community as well. While many had the benefit of the government’s support they still struggled to get by, but this lack of capital was the quintessential for the development to the movement and shaped its fundamental character.

“It is difficult not to feel nostalgic for an art world that was dead set against career strategizing and a time when expression in paint was untamed cathartic and sexy. This historical moment, of course, did not last long; it was done in by its own lack of commercial viability”

James Kelly, A Secret Place, 1998, Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, A Secret Place, 1998, Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

Another great revelation from this research and certainly a strategy to consider for current generations of painters, was the artists relationship to space or lack thereof. San Francisco’s abstract art scene was developing in the early 1950’s, and the places to exhibit artwork grew up in very grass roots manner. In todays rent crazed environment when all too many artists feel a lack of agency to exhibit their work, lessons can be learned from the early Bay Area abstractionists in making one’s own agency, by developing artist run or alternative exhibition spaces. While Kelly did end up in the highest echelons of art institutions, he like so many other painters began his career in modest artist run spaces. Three significant galleries from the pioneering period of San Francisco abstraction were: Delexi, King Ubu and East West Gallery, Kelly exhibited at all three.

James Kelly, Ornithology, 1998, Oil on canvas, 25 x 35 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Ornithology, 1998, Oil on canvas, 25 x 35 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

One of Hopps early partners was Jim Newman, Newman would form Dilexi gallery in San Francisco and would show Kelly’s work. According to Bill Dubin: “I asked… which gallery was the best in San Francisco, and he told me Dilexi.”

“The Dilexi Gallery began out of necessity– a deep-seated need to have a serious space for counterculture artists in the heart of vibrantly active, beatnik San Francisco. In 1958, Jim Newman and Bob Alexander filled this void with championing, free-spirited and nonconformist artists… Their use of new materials and non-traditional techniques eventually became their individual styles outside any singular art movement.”

King Ubu Gallery, 1952, Photography by Nata Piaskowski

King Ubu Gallery, 1952, Photography by Nata Piaskowski

Another artist run space on Filmore Street was the King Ubu Gallery.

Originally a 19th century stable it was an unusual setting for art. It was garage-like, with a pitched roof and exposed posts and heavy trusses. The floor was raw concrete, art would be hung on the internal beams of the walls against whitewashed timbers which formed the buildings outer shell. Sometimes the work would be hung upstretched and nailed directly to the wall.

“King Ubu was begun by the poet Robert Duncan and the painters Harry Jacobus and, who wished for a place to see experimental work…. The King Ubu Gallery opened in a large, converted garage in San Francisco (in)..1952. It was one of the first alternative spaces for art on the West coast,and it valued the striving and discoveries of the individual artist above any aesthetic Criteria”

The experimental gallery would last only a last a year but it the space would become the Six Gallery and it would remain an important and influential location in the development of the San Francisco Art scene.

The third gallery of seminal significance from the is early period of development in the San Francisco abstract art movement was the East West Gallery. The gallery was directed by Leonid Gechtoff, who was the mother of Sonia Gechtoff and was James Kelly’s mother-in-law. The significance of the gallery would be categorized at the time of her death by the critic R.H. Hagan by saying.

“The list of young artists who received their first shows at her gallery is too long to be given here. Here was one of the few galleries in town that was truly interested in what can be described as the “growing point” of art in this yeasty artistic community – including works by established artists in the process of exploring new and provocative lines of development as wells as works by newcomers whose development was only implicit in signs of their promise.”

Following the death of “Etya” in 1958, Kelly and Gechtoff would move to New York were they would continue to paint for the next five decades.

James Kelly, Sticky Fingers, 2002, Oil on canvas, 34 x 34 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

James Kelly, Sticky Fingers, 2002, Oil on canvas, 34 x 34 in. Courtesy of David Richard Gallery, Photography by Yao Zu Lu

In Kelly we see an artist driven by a courageous propensity to radically reinvent himself was wrought from the spirit of freedom which prevailed at the edge of America during San Francisco’s early days of abstract art. For Kelly Painting was clearly a necessity. There are others for whom the same is true and who will intuitively sympathize that often the journey of painting is more consequential that the destination. For those who like him find painting a necessity, thank you, we are better for it. WM

Bibliography:

Acton, David, The Stamp of Impulse: Abstract Expressionist Prints, The Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA, 2001, p. 112

Albright, Thomas, Art in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–1980 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985

Allen, Ken, Reflections on Walter Hopps in Los Angeles, X-Tra, Fall 2005, Vol. 8 No. 1

Aukeman, Anastasia, The Art Scene Rebels of San Francisco., Literary Hub. September 2, 2016

Blum, Irving, Oral History with Irving Blum 1977 May 31st – June 23rd, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, (Washington D.C.)

Dean, Charles, Brilliant Mistakes: James Kelly’s Deep Blue I, Art in Print, Vol. 5, No. 5

Hopkins, Henry J., Painting and Sculpture in California: The Modern Era, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1977

Grissom, Sarah, San Francisco, The Art Associations 77th Annual, Arts Magazine, 1958, Vol. 32, No. 8.

Kerr, Leslie, Then & Now, Documentaries on the California Beat Era, Bill Dubin’s memories of the Dilexi years

Hopps, Walter with Deborah Treisman, The Dream Colony, (Bloomsbury, New York and London)

Landauer, Susan, The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism, The University of California Press, 1996, p. 52

McChesney, Mary Fuller, A Period of Exploration, San Francisco, 1945-1950, Oakland Museum, 1973.

M.H.S, James Kelly, Bay Area Action Painting, (San Jose Museum of Art, 2004)

Moss, Stacey Mediating Abstraction and Figuration: The Paintings of James Kelly, 1952–1990 (Belmont, Calif.: The Wiegand Gallery, College of Notre Dame, 1990)

Obrist, Hans, Walter Hopps Hopps Hopps, Hans-Ulrich Obrist talks with Walter Hopps, Artforum, February 1996

Plagens, Peter, “Sunshine Muse: Contemporary Art on the West Coast”, Praeger Publishers, 1974

Sullivan, Missy, Ed., Collector’s Eye: Abstract Expressionist Prints, Forbes Collector, November 2005, Vol. 3, No. 11, p. 6.

Endnotes

1. Moss, Stacey Mediating Abstraction and Figuration: The Paintings of James Kelly, 1952–1990 (Belmont, Calif.: The Wiegand Gallery, College of Notre Dame, 1990), n.p.

2. Painting and Sculpture in California: The Modern Era, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1977, pp. 123, source: St. John, Terry, introduction to book A Period of Exploration, San Francisco 1945-1950, Fuller, Mary, McChesney, The Oakland Museum, California, 1973.

3. M.H.S, James Kelly, Bay Area Action Painting, (San Jose Museum of Art, 2004), n.p

4. Albright, Thomas, Art in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–1980 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), pp. 52.

5. Allen, Ken, Reflections on Walter Hopps in Los Angeles, X-Tra, Fall 2005, Vol. 8 No. 1

6. Obrist, Hans, Walter Hopps Hopps Hopps, Hans-Ulrich Obrist talks with Walter Hopps, Artforum, February 1996, pp, 40, 43, 62 – 63, 94, 193-194

7. Hopps, Walter with Deborah Treisman, The Dream Colony, (Bloomsbury, New York and London) pp. 46

8. Blum, Irving, Oral History with Irving Blum 1977 May 31st – June 23rd, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, (Washington D.C.) pp. 4

9. Duncan, Michael, Report from San Francisco, Bay Area Bravura, Art In America September 1996, pp. 45

10. Ibid. pp. 47

11. Kerr, Leslie, Then & Now, Documentaries on the California Beat Era, Bill Dubin’s memories of the Dilexi years, n.p.

12. Independent, Restaging the Legendary Dilexi Gallery, Four Los Angeles galleries unite: The Landing, Parker Gallery, Parrasch Heijnen gallery and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, August 2019

13. Wagstaff, Christopher, An Art of Wondering, The King Ubu Gallery, 1952 – 1953, Natsoulas Novel Gallery, Davis CA, 1989, pp. 7

14. Hagan, R.H, The Bay Window, The critical Review of the Arts, San Francisco, 1958, Vol.2 No. 8 pp 1, 3